The 21st-century Keller

family. Craig and Sandy are seated at center, with their

daughters Kristy Harden, left, and Rachel. In the rear from left

are Kim Werk, Craig’s sister; Dennis, his brother; and Priscilla

Keller Reynolds, his mother.

ARE WE GOING TO BE

BIGGER, SMARTER AND HEALTHIER THAN

OUR ANCESTORS

The New York Times: July 30, 2006: By GINA KOLATA

Valentin Keller enlisted in an all-German

unit of the Union Army in Hamilton, Ohio, in 1862. He was 26, a small,

slender man, 5 feet 4 inches tall, who had just become a naturalized

citizen. He listed his occupation as tailor.

A year later, Keller was honorably discharged, sick and broken. He had a

lung ailment and was so crippled from arthritis in his hips that he could

barely walk.

His pension record tells of his suffering. “His rheumatism is so that he is

unable to walk without the aid of crutches and then only with great pain,”

it says. His lungs and his joints never got better, and Keller never worked

again.

He died at age 41 of “dropsy,” which probably meant that he had congestive

heart failure, a condition not associated with his time in the Army. His

39-year-old wife, Otilia, died a month before him of what her death

certificate said was “exhaustion.”

People of Valentin Keller’s era, like those before and after them, expected

to develop chronic diseases by their 40’s or 50’s. Keller’s descendants had

lung problems, they had heart problems, they had liver problems. They died

in their 50’s or 60’s.

Now, though, life has changed. The family’s baby boomers are reaching middle

age and beyond and are doing fine.

“I feel good,” says Keller’s great-great-great-grandson Craig Keller. At 45,

Mr. Keller says he has no health problems, nor does his 45-year-old wife,

Sandy.

The Keller family illustrates what may prove to be one of the most striking

shifts in human existence — a change from small, relatively weak and sickly

people to humans who are so big and robust that their ancestors seem almost

unrecognizable.

New research from around the world has begun to reveal a picture of humans

today that is so different from what it was in the past that scientists say

they are startled. Over the past 100 years, says one researcher, Robert W.

Fogel of the University of Chicago, humans in the industrialized world have

undergone “a form of evolution that is unique not only to humankind, but

unique among the 7,000 or so generations of humans who have ever inhabited

the earth.”

And if good health and nutrition early in life are major factors in

determining health in middle and old age, that bodes well for middle-aged

people today. Investigators predict that they may live longer and with less

pain and misery than any previous generation.

“Will

old age for today’s baby boomers be anything like the old age we think we

know?” Dr. Barker asked. “The answer is no.”

Trying to Change a Pattern

Craig Keller does not know what to expect of his old age. But he is

optimistic by nature, and he knows he has already lived past the life span

of his beleaguered ancestor Valentin. He is 5-foot-9, 200 pounds and

exuberantly healthy.

He grew up in Hamilton, the same town on the Kentucky border where Valentin

lived, worshiped and was buried. And he still lives there, working as a

court bailiff, married to Sandy, whom he met when they were in second grade.

Now, married 25 years, the Kellers have two grown daughters, a lively black

dog and no complaints.

Craig and Sandy Keller had all the advantages of middle-class Americans of

their age: childhood vaccines, plenty of food, antibiotics when they fell

ill. Now, wanting to stay healthy, they walk in the evenings, try to eat

well and rely on their strong faith, which, they say, makes a big difference

to their health. And they enjoy life.

Mr. Keller pulls his wife’s tan Chevy Malibu into the driveway of his small,

immaculate house on a sidewalk-lined street. It is the same house that he

grew up in; he and Mrs. Keller bought it from Mr. Keller’s parents 22 years

ago. While Mrs. Keller brings out a snack of a homemade cheese ball,

crackers, sandwiches, fruit salad and brownies, Mr. Keller settles in to

marvel at the contrast between his comfortable life and the lives of his

ancestors.

For him, the idea of falling ill in his late 20’s and never working again is

unimaginable. He knows, though, that he is nearing the age when many of his

ancestors died. His father, Carl D. Keller, a lifelong smoker, developed

prostate cancer, then emphysema, and then lung cancer, which killed him at

age 65. His father’s father, Carl W. Keller, also a smoker, died of cancer

of the esophagus just after he turned 69. His grandfather on his mother’s

side died of cirrhosis of the liver at 55; his grandmother died at 56 of

breast cancer.

“They never got out of their 50’s and 60’s,” Mr. Keller said. “So that’s

kind of in the back of your mind.” He worries about his lungs, given his

family history. He had pneumonia once and has had bronchitis.

But, Mr. Keller reasons, he is so physically different from his ancestors —

he has never smoked and is so much healthier, so much better fed — that he

really thinks he will break the spell.

And if exercise is good for health, the Kellers certainly have exercised.

Mr. Keller displays a bookcase in their basement, crammed with athletic

trophies. Mrs. Keller’s are from baton twirling, Mr. Keller’s are from

baseball, basketball, softball and soccer. Their daughters, 19-year-old

Rachel and 22-year-old Kristy, got theirs cheerleading.

Mrs. Keller said that when she was her daughters’ age, “I didn’t think about

my health very much.”

“But later in my 30’s and toward my 40’s,” she said, “I started to think

about it. You try to eat right, you try to exercise. And you do see your

parents with illnesses. And you wonder about yourself. My mom had a

quadruple bypass when she was 75, and she had to have a pacemaker after

that. She’s now in her 80’s, but you do wonder.”

Was it genetic destiny or health habits that caused her mother’s heart

disease? Mrs. Keller asks herself. Her mother smoked for more than a decade,

finally quitting with great difficulty before Mrs. Keller was born. “She

said the Lord helped her,” Mrs. Keller said.

Mrs. Keller has never smoked. Concerned about heart disease, she had her

cholesterol level tested a few years ago and now takes medication to lower

it. She walks at lunch with the women in her office and after dinner with

her husband.

Her daughter Rachel, petite and quiet with a quick smile, is already

thinking about her family’s medical history. She worries about heart

disease, worries about lung disease. She has already had her cholesterol

level measured — it was normal. And she is shocked when people her age start

smoking.

“In high school, none of my friends smoked,” she said. “They came back from

their first year in college, and all of them did.”

“It’s hard to think about getting old when you’re young,” Rachel added. “But

when you see your family members — my grandpa died of lung cancer, my

grandparents on both sides had cancer. So it’s on my mind a lot of times.”

But still, the future is so distant it is almost unfathomable to her. “I

wonder what we’re going to be like when we’re old,” she mused.

Lives Plagued by Illness

Scientists used to say that the reason people are living so long these days

is that medicine is keeping them alive, though debilitated. But studies like

one Dr. Fogel directs, of Union Army veterans, have led many to rethink that

notion.

The study involves a random sample of about 50,000 Union Army veterans. Dr.

Fogel compared those men, the first generation to reach age 65 in the 20th

century, with people born more recently.

The researchers focused on common diseases that are diagnosed in pretty much

the same way now as they were in the last century. So they looked at

ailments like arthritis, back pain and various kinds of heart disease that

can be detected by listening to the heart.

The

first surprise was just how sick people were, and for how long.

Instead of inferring health from causes of death on death certificates, Dr.

Fogel and his colleagues looked at health throughout life. They used the

daily military history of each regiment in which each veteran served, which

showed who was sick and for how long; census manuscripts; public health

records; pension records; doctors’ certificates showing the results of

periodic examinations of the pensioners; and death certificates.

They discovered that almost everyone of the Civil War generation was plagued

by life-sapping illnesses, suffering for decades. And these were not some

unusual subset of American men — 65 percent of the male population ages 18

to 25 signed up to serve in the Union Army. “They presumably thought they

were fit enough to serve,” Dr. Fogel said.

Even teenagers were ill. Eighty percent of the male population ages 16 to 19

tried to sign up for the Union Army in 1861, but one out of six was rejected

because he was deemed disabled.

And the Union Army was not very picky. “Incontinence of urine alone is not

grounds for dismissal,” said Dora Costa, an M.I.T. economist who works with

Dr. Fogel, quoting from the regulations. A man who was blind in his right

eye was disqualified from serving because that was his musket eye. But, Dr.

Costa said, “blindness in the left eye was O.K.”

After the war ended, as the veterans entered middle age, they were rarely

spared chronic ailments.

“In the pension records there were descriptions of hernias as big as

grapefruits,” Dr. Costa said. “They were held in by a truss. These guys were

continuing to work although they clearly were in a lot of pain. They just

had to cope.”

Eighty percent had heart disease by the time they were 60, compared with

less than 50 percent today. By ages 65 to 74, 55 percent of the Union Army

veterans had back problems. The comparable figure today is 35 percent.

The steadily improving health of recent generations shows up in population

after population and country after country. But these findings raise a

fundamental question, Dr. Costa said.

“The question is, O.K., there are these differences, and yes, they are big.

But why?” she said.

“That’s the million-dollar question,” said David M. Cutler, a health

economist at Harvard. “Maybe it’s the trillion-dollar question. And there is

not a received answer that everybody agrees with.”

Outgrowing the Past

Don Hotchkiss, a civil engineer in Las Vegas and a descendant of Civil War

veterans, is an avid Civil War re-enactor. Early on, he and his brother

tried to sleep in an exact replica of one of the old tents.

It was too small, Mr. Hotchkiss said. He is six feet tall and stocky. His

brother, a police officer in Phoenix, is thinner, but 6-foot-2. The tents

were made for men who were average size then. “In the past 145 years, we’ve

ballooned up,” Mr. Hotchkiss said. At a recent meeting of a Las Vegas chapter of the Sons of Confederate

Veterans, eight burly men crowded into a library meeting room. All had

experienced the equivalent of the Civil War tent problem.

“At the re-enactments, all the directors, all the costume directors say the

re-enactors are just too darn big,” said George McClendon, a hefty

67-year-old retired airline pilot.

|

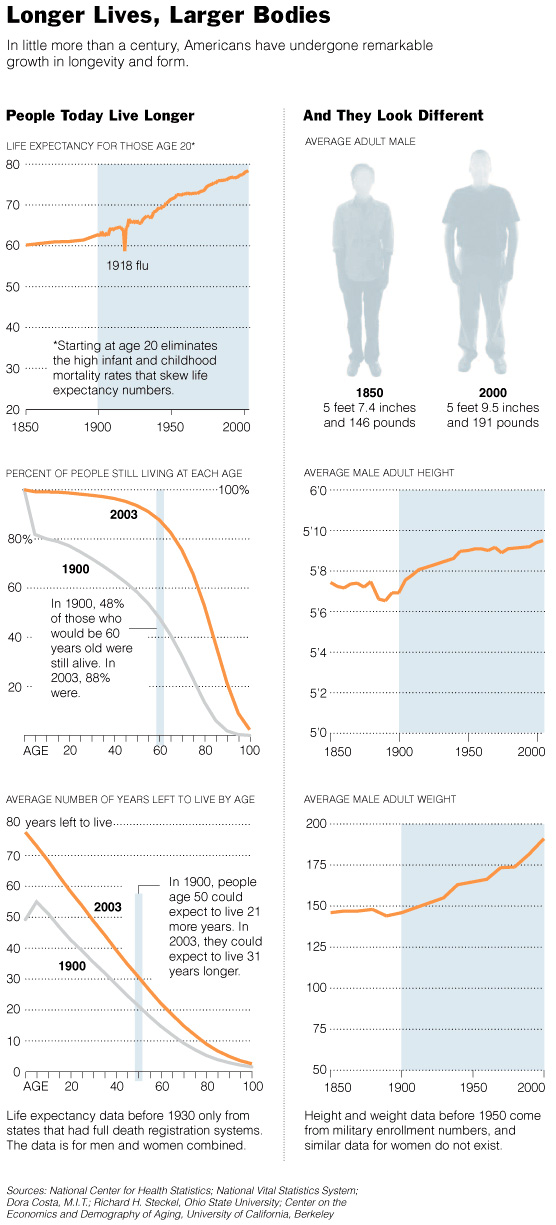

Mr. McClendon is right. Men living in the Civil War era had an average

height of 5-foot-7 and weighed an average of 147 pounds. That translates

into a body mass index of 23, well within the range deemed “normal.” Today,

men average 5-foot-9½ and weigh an average of 191 pounds, giving them an

average body mass index of 28.2, overweight and edging toward obesity.

Those changes, along with the great improvements in general health and life

expectancy in recent years, intrigued Dr. Costa. Common chronic diseases —

respiratory problems, valvular heart disease, arteriosclerosis, and joint

and back problems — have been declining by about 0.7 percent a year since

the turn of the 20th century. And when they do occur, they emerge at older

ages and are less severe.

The reasons, she and others are finding, seem to have a lot to do with

conditions early in life. Poor nutrition in early years is associated with

short stature and lifelong ill health, and until recently, food was

expensive in the United States and Europe.

Dr. Fogel and Dr. Costa looked at data on height and body mass index among

Union Army veterans who were 65 and older in 1910 and veterans of World War

II who were that age in the 1980’s. Their data relating size to health led

them to a prediction: the World War II veterans should have had 35 percent

less chronic disease than the Union Army veterans. That, they said, is

exactly what happened.

They

also found that diseases early in life left people predisposed to chronic

illnesses when they grew older.

“Suppose you were a survivor of typhoid or tuberculosis,” Dr. Fogel said.

“What would that do to aging?” It turned out, he said, that the number of

chronic illnesses at age 50 was much higher in that group. “Something is

being undermined,” he said. “Even the cancer rates were higher. Ye gods. We

never would have suspected that.”

Men who had respiratory infections or measles tended to develop chronic lung

disease decades later. Malaria often led to arthritis. Men who survived

rheumatic fever later developed diseased heart valves.

And stressful occupations added to the burden on the body.

People would work until they died or were so disabled that they could not

continue, Dr. Fogel said. “In 1890, nearly everyone died on the job, and if

they lived long enough not to die on the job, the average age of retirement

was 85,” he said. Now the average age is 62.

A century ago, most people were farmers, laborers or artisans who were

exposed constantly to dust and fumes, Dr. Costa said. “I think there is just

this long-term scarring.”

Searching for Answers

Dr. Barker of Oregon Health and Science University is intrigued by the

puzzle of who gets what illness, and when.

“Why do some people get heart disease and strokes and others don’t?” he

said. “It’s very clear that current ideas about adult lifestyles go only a

small way toward explaining this. You can say that it’s genes if you want to

cease thinking about it. Or you can say, When do people become vulnerable

during development? Once you have that thought, it opens up a whole new

world.”

It is a world that obsesses Dr. Barker. Animal studies and data that he and

others have been gathering have convinced him that health in middle age can

be determined in fetal life and in the first two years after birth.

His work has been controversial. Some say that other factors, like poverty,

may really be responsible. But Dr. Barker has also won over many scientists.

In one study, he examined health records of 8,760 people born in Helsinki

from 1933 to 1944. Those whose birth weight was below about six and a half

pounds and who were thin for the first two years of life, with a body mass

index of 17 or less, had more heart disease as adults.

Another study, of 15,000 Swedish men and women born from 1915 to 1929, found

the same thing. So did a study of babies born to women who were pregnant

during the Dutch famine, known as the Hunger Winter, in World War II.

That famine lasted from November 1944 until May 1945. Women were eating as

little as 400 to 800 calories a day, and a sixth of their babies died before

birth or shortly afterward. But those who survived seemed fine, says Tessa

J. Roseboom, an epidemiologist at the University of Amsterdam, who studied

2,254 people born at one Dutch hospital before, during and after the famine.

Even their birth weights were normal.

But now those babies are reaching late middle age, and they are starting to

get chronic diseases at a much higher rate than normal, Dr. Roseboom is

finding. Their heart disease rate is almost triple that of people born

before or after the famine. They have more diabetes. They have more kidney

disease.

That is no surprise, Dr. Barker says. Much of the body is complete before

birth, he explains, so a baby born to a pregnant woman who is starved or ill

may start life with a predisposition to diseases that do not emerge until

middle age.

The middle-aged people born during the famine also say they just do not feel

well. Twice as many rated their health as poor, 10 percent compared with 5

percent of those born before or after the famine.

“We asked them whether they felt healthy,” Dr. Roseboom said. “The answer to

that tends to be highly predictive of future mortality.”

But not everyone was convinced by what has come to be known as the Barker

hypothesis, the idea that events very early in life affect health and

well-being in middle and old age. One who looked askance was Douglas V.

Almond, an economist at Columbia University.

Dr. Almond had a problem with the studies. They were not of randomly

selected populations, he said, making it hard to know if other factors had

contributed to the health effects. He wanted to see a rigorous test — a

sickness or a deprivation that affected everyone, rich and poor, educated

and not, and then went away. Then he realized there had been such an event:

the 1918 flu.

The flu pandemic arrived in the United States in October 1918 and was gone

by January 1919, afflicting a third of the pregnant women in the United

States. What happened to their children? Dr. Almond asked.

He compared two populations: those whose mothers were pregnant during the

flu epidemic and those whose mothers were pregnant shortly before or shortly

after the epidemic.

To his astonishment, Dr. Almond found that the children of women who were

pregnant during the influenza epidemic had more illness, especially

diabetes, for which the incidence was 20 percent higher by age 61. They also

got less education — they were 15 percent less likely to graduate from high

school. The men’s incomes were 5 percent to 7 percent lower, and the

families were more likely to receive welfare.

The effects, Dr. Almond said, occurred in whites and nonwhites, in rich and

poor, in men and women. He convinced himself, he said, that there was

something to the Barker hypothesis.

Craig Keller hopes it is true. He looks back at the hard life of his

ancestors, even those of his great-grandfather and his grandfather, working

as painters, exposed to fumes. And, of course, there was poor Valentin

Keller, his Civil War ancestor, his health ruined by the time he was 30.

Today, Mr. Keller says, he is big and healthy, almost despite himself. He

would like to think it is because he tries to live well, but he is not so

sure, especially when he hears about what Dr. Barker and Dr. Fogel and the

others have found. Maybe it was his good fortune to have been born to a

healthy mother and to be well fed and vaccinated.

“I don’t know if we have as much control as we think we do,” he said.

The difference does not involve changes in genes, as far as is known, but

changes in the human form. It shows up in several ways, from those that are

well known and almost taken for granted, like greater heights and longer

lives, to ones that are emerging only from comparisons of health records.

The biggest surprise emerging from the new studies is that many chronic

ailments like heart disease, lung disease and arthritis are occurring an

average of 10 to 25 years later than they used to. There is also less

disability among older people today, according to a federal study that

directly measures it. And that is not just because medical treatments like

cataract surgery keep people functioning. Human bodies are simply not

breaking down the way they did before.

Even the human mind seems improved. The average I.Q. has been increasing for

decades, and at least one study found that a person’s chances of having

dementia in old age appeared to have fallen in recent years.

The proposed reasons are as unexpected as the changes themselves. Improved

medical care is only part of the explanation; studies suggest that the

effects seem to have been set in motion by events early in life, even in the

womb, that show up in middle and old age.

“What happens before the age of 2 has a permanent, lasting effect on your

health, and that includes aging,” said Dr. David and J. P. Barker, a professor

of medicine at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland and a

professor of epidemiology at the University of Southampton in England.

Each event can touch off others. Less cardiovascular disease, for example,

can mean less dementia in old age. The reason is that cardiovascular disease

can precipitate mini-strokes, which can cause dementia. Cardiovascular

disease is also a suspected risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease.

The effects are not just in the United States. Large and careful studies

from Finland, Britain, France, Sweden and the Netherlands all confirm that

the same things have happened there; they are also beginning to show up in

the underdeveloped world.

Of course, there were people in previous generations who lived long and

healthy lives, and there are people today whose lives are cut short by

disease or who suffer for years with chronic ailments. But on average, the

changes, researchers say, are huge.

Even more obvious differences surprise scientists by the extent of the

change.

In 1900, 13 percent of people who were 65 could expect to see 85. Now,

nearly half of 65-year-olds can expect to live that long.

People even look different today. American men, for example, are nearly

three inches taller than they were 100 years ago and about 50 pounds

heavier.

“We’ve been transformed,” Dr. Fogel said.

What next? scientists ask.

Today’s middle-aged people are the first

generation to grow up with childhood vaccines and with antibiotics. Early

life for them was much better than it was for their parents, whose early

life, in turn, was much better than it was for their parents.

(This is the first article in a series looking at the science of aging. Other

articles will explore the genetics of aging, body image and frailty, and who

ages well and why.)

Below are comparative

charts showing the changes occurring in human body and health..... |