|

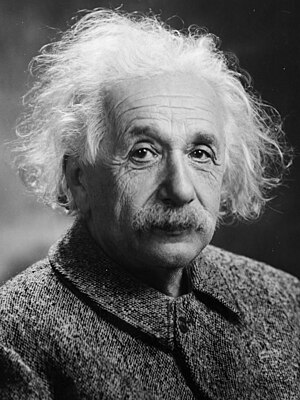

What Spacetime Is It?

NEW YORK TIMES: November 26, 2006: Dennis Overbye

In

a room somewhere in a building outside of time, for reasons he doesn’t quite

understand, Albert Einstein sits and works on his universal plan, plays his

violin, puffs a pipe and fends off an outraged Isaac Newton, among other

visitors. Into this scene comes an unnamed young woman with a tape recorder,

which might or might not work under these circumstances — her watch

apparently doesn’t — intent on getting an interview.

This setup didn’t inspire high hopes. Not that I hadn’t often wondered,

after years of following physics and even writing a biography that involved

serious time with Einstein’s personal correspondence, just what I’d have

asked the old man if I’d been granted a one-on-one. If, however, this

novel’s opening was just a contrivance to have Einstein explain the laws of

physics, I was willing to take a pass. Been there; done that.

But Jean-Claude Carričre comes with some serious mojo as a thinker and

writer, having worked with the likes of Peter Brook and Luis Buńuel on films

like “The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” and “Belle du Jour.” He’s

obviously worth risking a few hours with, and I’m happy to report that he

far exceeded my meager expectations.

“Please, Mr. Einstein,” unobtrusively

translated from the French by John Brownjohn, isn’t so much a novel about

physics as it is a novel about how people feel about physics — presumably Carričre, who gives his fictional Einstein all the best lines.

Some, in

fact, are like open doors you could wander through and never come out of:

“Being distrustful of those who persistently deceived us, we developed the

habit of also distrusting the night, which enshrouded us, or so we thought,

in gloom and illusion. We put our faith in light alone.”

In its uncounted hours of conversation, “Please, Mr. Einstein” touches down

lightly and charmingly on some of the thorniest philosophical consequences

of Einstein’s genius and, by extension, the scientific preoccupations of the

20th century while scrolling through Einstein’s life.:

- the nature of reality,

- the fate of causality,

- the

comprehensibility of nature,

- the limits of the mind

It’s easy to see this novel as the germ of a future playlet or movie along the lines of Steve Martin’s “Picasso at the Lapin

Agile” or the play and movie “Insignificance,” which featured a mythical

Einstein in a hotel room with Marilyn Monroe.

I like Carričre’s Einstein. He’s frank, down to earth and not prone to

cosmic mustiness. He’s actually worn an Einstein T-shirt and admits he’s

happy to be talking to a woman, especially a woman from the 21st century,

because that means his godchild, the atomic bomb, hasn’t destroyed

civilization — yet. “I think better when eyes like yours are looking at me,”

he tells her, “and when I’m talking to them.”

|

He’s also happy to be able to correct the record on some of

his most quoted statements, including my favorite,

- “The most incomprehensible thing

about the universe is its comprehensibility. What is comprehensible is

that the universe is incomprehensible.”

Now he thinks the opposite might be closer to the truth.

Among the features of Einstein’s unusual office are doors he seems able to

open on any time and place. At one point, discussing his years in Germany,

he and his visitor step out into:

- A Nazi book-burning.

- Another excursion

provides the surprising climax to an amusing side plot about Newton, who

just doesn’t get relativity and quantum theory and keeps pestering Einstein

to explain what was so wrong with the clockwork world he described in the

17th century.

- Finally, exasperated, Einstein calls Newton over and opens a

door on the atomic blast that destroyed Hiroshima.

- Newton’s wig flutters in

the wind from the shock wave. He stares, aghast, then slowly turns

transparent and disappears.

- Newton’s universe is truly, undeniably dead, and

so his sojourn in this intellectual aerie is over.

The rest of what you might call a plot is devoted to the skeletal reliving

of Einstein’s years and the progression of his quest for the ultimate

equation, which leads into deeper and more frustrating questions, none of

which will be answered here.

“Only the adepts of ignorance consider

themselves satisfied once and for all. When one knows nothing, it’s

forever,” this Einstein says, perhaps speaking of certain modern political

figures. “All knowledge leads to further obscurities, it’s a well-known

fact.”

The brick wall that Einstein hit in his own lifetime was quantum theory,

with its message that on the atomic level events happen randomly and without

explanation. He famously rejected it by saying that

God didn’t play dice.

Here he elaborates:

“You asked me to explain, and I told you that explaining

is the hardest thing in the world. Now do you see why? Because I’d have to

explain that we must give up explaining. And I never would! It would mean

going against all that made up my life.”

It’s hard not to wonder what event or discovery could make Einstein turn

pale and disappear, ending his universe as definitely as the atomic massacre

in Hiroshima said fini to Newton’s. It could be as incomprehensible to us as

calculus is to a dog. It could happen tomorrow or in a hundred years. In the

face of this, Einstein shrugs and goes back to work. What else can he do?

In Martin’s play, Einstein and Picasso match wits until they’re both shown

up by Elvis, in a show-stopping surprise appearance. I missed seeing Elvis

or Marilyn here.

Carričre’s slice of the afterlife lacks the kind of

cross-cultural mischief that would have put Einstein and science in their

place. I love Einstein, and he might be the king of the universe. But he’s

still not quite king of the world.

Dennis Overbye is a science correspondent for The Times. His most recent

book is “Einstein in Love: A Scientific Romance.”

PLEASE, MR. EINSTEIN: By Jean-Claude Carričre;

Translated by John Brownjohn; 186 pp. Harcourt. $22.

E-Mail

Print |