Winter solstice

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- This article is about the astronomical and

cultural event of winter's solstice, also known as

midwinter. For other uses, see

Winter solstice (disambiguation),

Midwinter (disambiguation) or also see

Solstice.

Winter Solstice

Fire kept burning through the longest night of the

year

Also called

Midwinter,

DongZhì,

Yule,

Sabe Cele/Yalda,

Soyal, Te?ufat ?ebet, Seva Zistanê, Solar New

Year, Longest Night

Observed by

Various cultures, ancient and modern

Type

Cultural, Seasonal, Astronomical

Significance

Astronomically marks the middle or beginning of

winter, interpretation varies from culture to

culture, but most hold a recognition of rebirth

Date

The

Solstice of

Winter

December 21 or

22 (NH)

June 21 or

22 (SH)

2007 date

December 22 (UTC

North)

June 21 (UTC

South)

2008 date

December 21 (UTC

North)

June 20 (UTC

South)

Celebrations

Festivals, spending time with loved ones,

feasting, singing, dancing, fire in the hearth

Related to

Winter Festivals and the

Solstice

UTC Date and Time of

Solstice

year

Solstice

June

Solstice

Dec

day

time

day

time

2007

21

18:06

22

06:08

2008

20

23:59

21

12:04

2009

21

05:45

21

17:47

2010

21

11:28

21

23:38

2011

21

17:16

22

05:30

2012

20

23:09

21

11:11

2013

21

05:04

21

17:11

2014

21

10:51

21

23:03

The

winter solstice occurs at the instant when the

Sun's

position in the sky is at its greatest angular distance on

the other side of the

equatorial plane as the observer. Depending on the shift

of the calendar, the event of the Winter

solstice occurs sometime between

December 20 and

23 each year in the

Northern hemisphere, and between

June 20 and

23 in the

Southern Hemisphere, and the winter solstice occurs

during either the

shortest day or the

longest

night of the year (not to be confused with the

darkest day or nights). Though the Winter Solstice lasts

an instant, the term is also used to refer to the full

24-hour period.

Worldwide, interpretation of the event has varied from

culture to culture, but most cultures have held a

recognition of rebirth, involving

holidays,

festivals, gatherings,

rituals or other

celebrations around that time.[1]

The word

solstice derives from

Latin

sol (Sun) and

sistere (stand still),

Winter Solstice meaning

Sun stand still in winter.

[edit]

Date

Calendrically, in most countries the time of the winter

solstice is considered as midwinter. This is evident in

calendars as far back as

Ancient Egypt, whose system of seasons was gauged

according to the flooding of the Nile. For Celtic countries,

such as

Ireland, the calendarical winter season has

traditionally begun

November 1 on

All Hallows or

Samhain. Winter ends and spring begins on

Imbolc or

Candlemas, which is

February 1 or

2. This calendar system of seasons may be based on the

length of days exclusively. Most

East Asian cultures define the seasons by

solar terms, with

Dong zhi at the Winter solstice as the middle or

"Extreme" of winter. This system is based on the sun's tilt.

Some Midwinter festivals have occurred according to

lunar calendars and so took place on the night of

Hoku (Hawaiian:

the full moon closest to the winter solstice). And many

European

solar calendar Midwinter celebrations still centre upon

the night of

December 24th leading into the

25th in the north, which was considered to be the winter

solstice upon the establishment of the

Julian calendar. In Jewish culture,

Te?ufat Tevet, the day of the winter solstice, is

historically known as the first day of the "stripping time"

or winter season.

Persian cultures also recognize it as the beginning of

winter. Recently, many United States calendars have marked

the date on which the winter solstice occurs as the

Astronomical First day of winter as a reference to

the

Tekufah.

Since the time when the 25th was established as the

solstice in Europe the difference between the Julian

calendar year (365.2500 days) and the

tropical year (365.2422 days) moved the day associated

with the actual astronomical solstice forward approximately

three days every four centuries until

1582 when

Pope Gregory XIII changed the calendar bringing the

northern winter solstice to around December 21st. In the

Gregorian calendar the solstice still moves around a

bit, but only about one day in 3000 years.

The figures above show the differences between the Gregorian

calendar (Figure 1: using 1 leap year per 4 years) and

Persian Persian Jalali calendar (Figure 2: using the

33-year arithmetic approximation) in reference to the actual

yearly time of the winter solstice of the northern

hemisphere, the December solstice. The Y axis is

"days error" and the X axis is Gregorian calendar years.

Each point represents a single date on a given year. The

error shifts by about 1/4 day per year, and is corrected by

a leap year every 4th year regularly, and in the case of the

Persian calendar also one 5 year leap period to complete a

33-year cycle, keeping the Persian winter solstice holiday

on the same day every year.

[edit]

History & Cultural significance

Astronomical events, which during ancient times allowed

for the scheduling of mating, sowing of crops and metering

of winter reserves between harvests, show how various

cultural mythologies and traditions have arisen. On the

night of Winter Solstice, as seen from a northern sky, the

three stars in

Orion's belt align with the brightest star in the

Eastern sky

Sirius to show where the Sun will rise in the morning

after Winter Solstice. Until this time, the Sun has

exhibited since

Summer Solstice a decreasing arc across the Southern

sky. On Winter Solstice, the Sun ceased to decline in the

sky and the length of daylight reaches its minimum for three

days. At such a time, the Sun begins its ascent and days

grow longer. Thus the interpretation by many cultures of a

sun reborn and a return to light. This return to light is

again celebrated (at the

vernal equinox, when the length of day equals that of

night.

The solstice itself may have remained a special moment of

the annual cycle of the year since

neolithic times. This is attested by physical remains in

the layouts of late Neolithic and Bronze Age archaeological

sites like Stonehenge in Britain and Brú na Bóinne (New

Grange) in Ireland. The primary axes of both of these

monuments seem to have been carefully aligned on a

sight-line framing the winter solstice sunrise (New

Grange)and the winter solstice sunset (Stonehenge). The

winter solstice may have been immensely important because

communities were not assured to live through the winter, and

had to be prepared during the previous nine months.

Starvation was common in winter between January to

April, also known as the

famine months. In temperate climates, the midwinter

festival was the last feast

celebration, before deep winter began. Most cattle were

slaughtered so they would not have to be fed during the

winter, so it was nearly the only time of year when a supply

of fresh meat was available. The majority of

wine and

beer made during the year was finally

fermented and ready for drinking at this time. The

concentration of the observances were not always on the day

commencing at

midnight or at

dawn, but the beginning of the pre-Romanized day, which

falls on the previous

eve.[2]

[edit]

Explanations for parallel

traditions

[edit]

Symbolic

Often since the event is observed as the reversal of the

Sun's

ebbing presence in the sky, concepts of the birth or

rebirth of

sun gods have been common and, in cultures using winter

solstitially based cyclic calendars, the year as reborn

has been celebrated with regard to

life-death-rebirth deities or new beginnings such

as

Hogmanay's redding, a

New Years cleaning tradition. Also reversal is

another usual theme as in

Saturnalia's slave and master reversals.

[edit]

Migration and appropriation

Many outside traditions are often adopted by neighboring

or invading cultures. Some historians will often assert that

many traditions are directly derived from previous ones

rooting all the way back to those begun in the

cradle of civilization or beyond, much in a way that

correlates to speculations on the

origins of languages.

[edit]

Therapeutic

Even in modern cultures these gatherings are still valued

for emotional comfort, having something to look forward to

at the darkest time of the year. This is especially the case

for populations in the near

polar regions of the hemisphere. The depressive

psychological effects of winter on individuals and

societies for that matter, are for the most part tied to

coldness, tiredness,

malaise, and inactivity. Winter

weather, plus being indoors causes negative

ion

deficiency which decreases

serotonin levels resulting in

depression and tiredness. Also, getting insufficient

light in the short winter days increases the secretion of

melatonin in the body, off balancing the

circadian rhythm with longer sleep. Exercise,

light therapy, increased negative

ion

exposure (which can be attained from plants and well

ventilated flames burning wood or

beeswax) can reinvigorate the body from its seasonal

lull and relieve winter blues by shortening the

melatonin secretions, increasing serotonin and temporarily

creating a more even sleeping pattern. Midwinter festivals

and celebrations occurring on the longest night of the year,

often calling for

evergreens, bright illumination, large ongoing fires,

feasting, communion with close ones, and evening physical

exertion by dancing and singing are examples of cultural

winter therapies that have evolved as traditions since the

beginnings of civilization. Such traditions can stir the

wit,

stave off malaise, reset the

internal clock and rekindle the human spirit.[3][4]

[edit]

Observances

The following is an alphabetical list of observances

believed to be directly linked to the winter solstice. For

other Winter observances see

List of winter festivals.:

[edit]

Amaterasu celebration, Requiem of

the Dead (7th

century

Japan)

-

In late

seventh century

Japan, festivities were held to celebrate the

reemergence of

Amaterasu or Amateras (Hindu),

the

sun goddess of

Japanese mythology, from her seclusion in a cave.

Tricked by the other gods with a loud celebration, she peeks

out to look and finds the image of herself in a mirror and

is convinced by the other gods to return, bringing sunlight

back to the universe.

Requiems for the dead were held and

Manzai and Shishimai were performed throughout the

night, awaiting the sunrise. Aspects of this tradition have

continued to this day on New Years.[5]

[edit]

Beiwe Festival (Sámi

of

Northern

Fennoscandia)

- See also:

Beiwe

The

Saami, indigenous people of

Finland,

Sweden and

Norway, worship Beiwe, the sun-goddess of

fertility and sanity. She travels through the sky in a

structure made of reindeer bones with her daughter,

Beiwe-Neia, to herald back the greenery on which the

reindeer feed. On the winter solstice, her worshipers

sacrifice white female animals, and with the meat, thread

and sticks, bed into rings with ribbons. They also cover

their doorposts with butter so Beiwe can eat it and begin

her journey once again.[6]

[edit]

Choimus, Chaomos (Kalash

of

Pakistan)

In the ancient traditions of the

Kalash people of

Pakistan, during winter solstice, a

demigod returns to collect prayers and deliver them to

Dezao, the supreme being. "During this celebrations women

and girls are purified by taking ritual baths. The men pour

water over their heads while they hold up bread. Then the

men and boys are purified with water and must not sit on

chairs until evening when goat's blood is sprinkled on their

faces. Following this purification, a great festival begins,

with singing, dancing, bonfires, and feasting on goat tripe

and other delicacies".[7]

[edit]

Christmas, Natalis Domini (4th

century

Rome,

11th century

England,

Christian)

-

Christmas or Christ's Mass is one of most

popular

Christian celebrations as well as one of the most

globally recognized midwinter celebrations. Christmas is the

celebration of the birth of the

God

Incarnate or

Messiah,

Yeshua of

Nazareth, later known as Jesus Christ. The birth is

observed on December 25th, which was the winter solstice

upon establishment of the Julian Calendar in

45

BC. Banned by the

Catholic Church in its infancy as a

pagan, or non-Abrahamic, practice stemming out of

the Sol Invictus celebrations, Christians revitalized

its recognition as an authentic Christian festival in

various cultures within the past several hundred years,

preserving much of the folklore and traditions of local

pagan festivals. So today, the old festivals such as

Jul, ?????? and Karácsony,

are still celebrated in many parts of Europe, but the

Christian Nativity is now often representational of the

meaning. This is why

Yule and Christmas are considered

interchangeable in

Anglo-Christendom.

Universal activities include feasting,

midnight masses and singing

Christmas carols about the Nativity. Good deeds

and gift giving in the tradition of

St. Nicholas by not admitting to being the actual gift

giver is also observed by some countries. Many observe the

holiday for

twelve days leading up to the

Epiphany.

[edit]

Deuorius Riuri (Gaul)

Deuorius Riuri was the annual great divine

winter feast, observed by the

Coligny Calendar. The lunisolar Coligney Midwinter

returned to solar alignment every two and a half years.[8]

[edit]

Deygan (Zoroastrian)

The last day of the Persian month Azar is the longest

night of the year, when the forces of

Ahriman are assumed to be at the peak of their strength.

While the next day, the first day of the month Dey

known as khoram ruz or khore ruz (the day of

sun) belongs to

Ahura Mazda, the Lord of Wisdom. Since the days are

getting longer and the nights shorter, this day marks the

victory of Sun over the darkness. The occasion was

celebrated in the ancient Persian Deygan Festival

dedicated to Ahura Mazda, and

Mithra on the first day of the month Dey.[9]

[edit]

DongZhì Festival, Toji Festival

(East

Asia,

Vietnam, and

Buddhist)

Families eat pink and white

tangyuan, symbolizing family unity and

prosperity.

Families eat pink and white

tangyuan, symbolizing family unity and

prosperity.

-

The Winter Solstice Festival or The Extreme of

Winter (Chinese

and

Japanese: ??;

Korean: ??;

Vietnamese: Ðông chí)

(Pinyin:

Dong zhì), (Romaji:

Toji) is one of the most important festivals

celebrated by the Chinese and other East Asians during the

dongzhi

solar term on or around

December 21 when sunshine is weakest and daylight

shortest; i.e., on the first day of the dongzhi solar

term. The origins of this festival can be traced back to the

Yin and Yang philosophy of balance and harmony in the

cosmos. After this celebration, there will be days with

longer daylight hours and therefore an increase in positive

energy flowing in. The philosophical significance of this is

symbolized by the

I Ching

hexagram

fù (?, "Returning"). Traditionally, the Dongzhi

Festival is also a time for the family to get together. One

activity that occurs during these get togethers (especially

in the southern parts of China and in

Chinese communities overseas) is the making and eating

of

Tangyuan (??, as pronounced in

Cantonese;

Mandarin

Pinyin: Tang Yuán) or balls of glutinous rice,

which symbolize reunion.

[edit]

Goru (Dogon

of

Mali)

Goru is the (December) winter solstice ceremony of

the

Pays Dogon of

Mali. It is the last harvest ritual and celebrates the

arrival of humanity from the sky god,

Amma, via

Nommo inside the Aduno Koro, or the "Ark of the

World".[10]

[edit]

Hogmanay (Scotland)

-

The

New Years Eve celebration of Scotland is called

Hogmanay. The name derives from the old Scots name for

Yule gifts of the Middle Ages. The early Hogmanay

celebrations were originally brought to Scotland by the

invading and occupying

Norse who celebrated a solstitial new year (England

celebrated the new year on

March 25th). In 1600 with the Scottish application of

the

January 1st New year and the churches persistent

abolition of the solstice celebrations, the holiday

traditions moved to

December 31. The festival is still referred to as the

Yules by the

Scots of the

Shetland Islands who start the festival on December 18th

and hold the last tradition, (a

Troll chasing ritual) on January 18th. The most

widespread Scottish custom is the practice of

first-footing which starts immediately after

midnight on New Years. This involves being the first person

(usually tall and dark haired) to cross the threshold of a

friend or neighbor and often involves the giving of symbolic

gifts such as salt (less common today), coal,

shortbread,

whisky, and black bun (a fruit pudding) intended to

bring different kinds of luck to the householder. Food and

drink (as the gifts, and often

Flies cemetery) are then given to the guests.[11]

[edit]

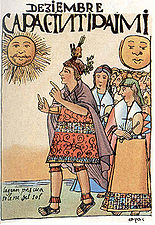

Inti Raymi (Inca,

Peru)

-

The Inti Raymi or Festival of the Sun was a

religious ceremony of the

Inca Empire in honor of the sun god

Inti. It also marked the winter solstice and a new year

in the

Andes of the

Southern Hemisphere. One ceremony performed by the Inca

priests was the tying of the sun. In

Machu Picchu there is still a large column of stone

called an Intihuatana, meaning "hitching post of the

sun" or literally for tying the sun. The ceremony to

tie the sun to the stone was to prevent the sun from

escaping. The

Spanish conquest, never finding Machu Picchu, destroyed

all the other intihuatana, extinguishing the sun tying

practice. The

Catholic Church managed to suppress all Inti festivals

and ceremonies by

1572. Since

1944, a theatrical representation of the Inti Raymi has

been taking place at

Sacsayhuamán (two km. from

Cusco) on

June 24 of each year, attracting thousands of local

visitors and

tourists. The

Monte Alto culture may have also had a similar

tradition.[12][13]

[edit]

Junkanoo, Jonkonnu, John Canoe

(West

Africa,

Bahamas,

Jamaica,

19th-century

North Carolina)

-

Junkanoo, in the Bahamas, Junkunno or

Jonkanoo, in Jamaica, is a fantastic masquerade, parade

and street festival, believed to be of West African origin.

It is traditionally performed through the streets towards

the end of December, and involves participants dressed in a

variety of fanciful

costumes, such as the Cow Head, the

Hobby Horse, the Wild Indian, and the

Devil. The parades are accompanied by bands usually

consisting of

fifes,

drums, and

coconut

graters used as scrapers, and Jonkanoo songs are also

sung. A similar practice was once common in coastal North

Carolina, where it was called John Canoe, John

Koonah, or John Kooner. John Canoe was likened to

the

wassailing tradition of

medieval Britain. Both John Canoe and wassailing bear

strong resemblance to the social inversion rituals that

marked the ancient Roman celebration of

Saturnalia.

[edit]

Karachun (Ancient

Western Slavic)

-

Karachun, Korochun or Kracún was a

Slavic holiday similar to

Halloween as a day when the

Black God and other evil spirits are most potent. It was

celebrated by

Slavs on the longest night of the year. On this night,

Hors, symbolising old sun, becomes smaller as the days

become shorter in the Northern Hemisphere, and dies on

December 22nd, the December solstice. It is said to be

defeated by the dark and evil powers of the Black God. In

honour of the god, Hors, Slavs danced a ritual chain-dance

which was called the horo. Traditional chain-dancing

in

Bulgaria is still called horo. In

Russia and

Ukraine, it is known as

khorovod. On

December 23rd Hors is resurrected and becomes the new

sun,

Koleda. Modern scholars tend to associate this holiday

with the

ancestor worship. On this day,

Western Slavs burned fires at cemeteries to keep their

loved ones warm, they organized dinings in the honor of the

dead so as they would not suffer from hunger. They also lit

wooden logs at local crossroads.

[edit]

Koleda, ??????, Sviatki, Dazh Boh

(Ancient

Eastern Slavic and

Sarmatian)

This article or section is

in need of attention from an expert on the subject.

WikiProject History or the

History Portal may be able to help recruit one.

If a more appropriate

WikiProject or

portal exists, please adjust this template

accordingly.

In ancient Slavonic cultures, the festival of Kaleda

began at Winter Solstice and lasted for ten days. In Russia,

this festival was later applied to

Christmas Eve but most of the practices were lost after

the

Soviet Revolution. Each family made a fire in their

hearth and invited their personal household Gods to join in

the festivities. Children disguise themselves on evenings

and nights and as

Koledari, visited houses and sang wishes of good

luck, like

Shchedryk, to hosts. As a reward, they were given

little gifts, a tradition called Kolyadovanie, much

like the old

wassailing or

mummers Tradition.[14][15]

[edit]

Lenæa, Brumalia (Ancient

and

Hellenistic Greece,

Roman Kingdom)

-

In the

Aegean civilizations, the exclusively female midwinter

ritual, Lenaea or Lenaia, was the Festival

of the Wild Women. In the forest, a man or bull

representing the harvest god,

Dionysus, was torn to pieces and eaten by

Maenads. Later in the ritual, a baby, representing

Dionysus reborn, was presented. The Ageans dedicated their

first month of the Delian calendar, Lenaion, to the

festival's name. By

classical times, the human sacrifice had been replaced

by that of a goat and the women's role had changed to that

of funeral mourners and observers of the birth. Wine

miracles were performed by the priests, in which priests

would seal water or juice into a room overnight and the next

day it would have turned into wine. The miracle was said to

have been performed by Dionysus and the

Lenaians. By the

5th century BC the ritual had become a

Gamelion festival for theatrical competitions, often

held in Athens in the Lenaion theater. The festival

influenced Brumalia which was an

ancient Roman solstice festival honoring

Bacchus, generally held for a month and ending

December 25. The festival included drinking and

merriment. The name is derived from the Greek word bruma,

meaning "shortest day", though the festivities almost always

occurred at night.[16][17][18]

[edit]

Lucia, Feast of St. Lucy (Ancient

Swedish,

Scandinavian

Lutheran,

Eastern Orthodox)

Lucia or Lussi Night happened on

December 13, what was supposed to be the longest night

of the year. The feast was later appropriated by the

Catholic Church in the

16th century as

St. Lucy's Day. It was believed in the

folklore of Sweden that if people, particularly

children, did not carry out their chores, the female

demon, the Lussi or Lucia die dunkle would

come to punish them.[19]

[edit]

Makara Sankranti (India

and

Nepal,

Hindu)

-

Makara Sankranti, celebrated at the beginning of

Uttarayanais, is the only Hindu festival which is

based on the Celestial calendar rather than the Lunar

calendar. The

Zodiac having drifted from the solar calendar has caused

the festival to now occur in mid January. In

Assam it is called Magh Bihu (the First day of

Magh), in

Punjab, Lohri and in Maharshtra it is called

Tilgul, but the place where it is celebrated with much

pomp is Andhra Pradesh, where the festival is celebrated for

3 days and is more of a cultural festival unlike an

auspicious day as in other parts of india. In some parts of

India, the festival is celebrated by taking dips in the

Ganga or any river and offering water to the Sun god.

The dip is said to purify the self and bestow

punya. In many countries, families fly

kites from their roofs all day and into the night. In

Assam on Bihu Eve or Uruka families build

bhelaghar, house like structures, and separate large

bhelaghar are built by the community as a whole. Twine of

sorts are tied around fruit trees. Out of tradition, fuel is

stolen for the final ceremony, when all the bhelaghar are

burned. Their remains are then placed at the fruit trees.

Special

puja is offered as a thanksgiving for good harvest.

Since the festival is celebrated in the mid winter, the food

prepared for this festival are such that they keep the body

warm and give high energy.

Laddu of til made with Jaggery (Gur)is specialty

of the festival.[20]

[edit]

Meán Geimhridh, Celtic Midwinter

(Celtic,

Ancient Welsh,

Neodruidic)

Meán Geimhridh (Irish tr: Midwinter) or

Grianstad an Gheimhridh (Ir tr: Winter solstice) is a

name sometimes used for hypothetical Midwinter rituals or

celebrations of the

Proto-Celtic

Neolithic tribes,

Celts, and late

Druids. In

Ireland's calendars, the solstices and

equinoxes all occur at about midpoint in each

season. The passage and chamber of

Newgrange (Pre-Celtic or possibly Proto-Celtic

3,200 BC), a tomb in Ireland, are illuminated by the winter

solstice sunrise. A shaft of sunlight shines through the

roof box over the entrance and penetrates the passage to

light up the chamber. The dramatic event lasts for 17

minutes at dawn from the 19th to the 23rd of December.

The point of roughness is the term for the winter

solstice in Wales which in ancient

Welsh mythology, was when

Rhiannon gave birth to the sacred son,

Pryderi.

[edit]

Wren day (Celtic,

Irish,

Welsh,

Manx)

-

- For an unknown period, Lá an Dreoilín or

Wren day has been celebrated in Ireland, The

Isle of Man and

Wales on

December 26. Crowds of people, called

wrenboys, take to the roads in various parts of

Ireland, dressed in motley clothing, wearing masks or

straw suits and accompanied by musicians supposedly in

remembrance of the festival that was celebrated by the

Druids. Previously the practice involved the killing

of a

wren, and singing songs while carrying the bird from

house to house, stopping in for food and merriment.

[edit]

Alban Arthan (Neodruidic)

-

- In

England, during the

18th century, there was a revival of interest in

Druids. Today, amongst

Neo-druids, Alban Arthan (Welsh tr. light

of Winter but derived from Welsh poem, Light of

Arthur) is celebrated on the winter solstice with a

ritualistic festival, and gift giving to the needy.

[edit]

Midvinterblót (Swedish

folk religion)

-

In

Sweden and many surrounding parts of

Europe,

polytheistic tribes celebrated a Midvinterblot or

mid-winter-sacrifice, featuring both animal and human

sacrifice. The

blot was performed by

goði, or priests, at certain cult sites, most of

which have churches built upon them now. Midvinterblot paid

tribute to the local gods, appealing to them to let go

winter's grip. The

folk tradition was finally abandoned by

1200, due to

missionary persistence.

[edit]

Modranicht, Modresnach (Anglo-Saxon,

Germanic)

The Night of Mothers or Mothers' Night was

an

Anglo-Saxon and

Germanic feast. It was believed that dreams on this

night foretold events in the upcoming year. While it may

originally have occurred the night before

Samhain according to a lunar calendar, it has moved

around quite a bit in the year. By

730,

It was thought by

Bede to be observed by the

Anglicans on the winter solstice. After the reemergence

of Christmas in

Britain it was recognized by many as one of the

12 Days of Christmas.[21][22]

[edit]

Perchta ritual (Germania,

Alps)

-

Early

Germans (c.500-1000)

considered the Norse goddess,

Hertha or Bertha to be the goddess of Light,

Domesticity and the home. They baked yeast cakes shaped like

shoes, which were called Hertha's slippers, and

filled with gifts. "During the Winter Solstice houses were

decked with fir and evergreens to welcome her coming. When

the family and serfs were gathered to dine, a great altar of

flat stones was erected and here a fire of fir boughs was

laid. Hertha descended through the smoke, guiding those who

were wise in saga lore to foretell the fortunes of those

persons at the feast".[23]

There are also darker versions of Perchta which terrorize

children along with

Krampus. Many cities had practices of dramatizing the

gods as characters roaming the streets. These traditions

have continued in the rural regions of the

Alps, as well various similar traditions, such as

Wren day, survived in the

Celtic nations until recently.

[edit]

Rozhanitsa Feast (12th

century

Eastern Slavic

Russian)

In twelfth century

Russia, the eastern

Slavs worshiped the winter mother goddess, Rozhnitsa,

offering bloodless sacrifices like honey, bread and cheese.

Bright colored winter embroideries depicting the antlered

goddess were made to honor the Feast of Rozhanitsa in

late December. And white, deer shaped cookies were given as

lucky gifts. Some Russian women continued the observation of

these traditions into the 20th century.[24]

[edit]

Shabe Celle, ???? , Yalda (2nd

millenium BC

Persian,

Iranian)

-

Derived from a pre-zoroastrian festival, Shabe Chelle

is celebrated on the eve of the first day of winter in the

Persian calendar, which always falls on the solstice.

Yalda is the most important non-new-year Iranian festival in

modern-day Iran & it has been long celebratd in Iran by all

ethnic/religious groups. According to Persian mythology,

Mithra was born at the end of this night after the long

expected defeat of darkness against Light. "Shabe Chelle" is

now an important social occasion, when family and friends

get together for fun and merriment. Usually families gather

at their elders homes. Different kinds of dried fruits,

nuts, seeds and fresh winter fruits are consumed. The

presence of dried and fresh fruits is reminiscence of the

ancient feasts to celebrate and pray to the deities to

ensure the protection of the winter crops.

Watermelons,

Persimmons &

Pomegranates are traditional symbols of this

celebration, all representing the Sun. It used to be

customary to keep awake the Yalda night untill sunrise

eating, drinking, listenning to stories & poems, but this is

no longer very common as most people have things to do on

the next day. During the early Roman empire many

Syric Christians fled from persecution into the

Sassanid Empire of Persia, introducing the term Yalda,

meaning birth, causing Shabe Yalda to became

synonymous with Shabe Chelle.

[25]

[edit]

Sanghamitta Day (Buddhist)

Sanghamitta is in honor of the

Buddhist nun who brought a branch of the

Bodhi tree to

SriLanka where it has flourished for over 2,000 years.

[edit]

Saturnalia, Chronia (Ancient

Greek,

Roman Republic)

-

Originally Celebrated by the Ancient Greeks as Kronia

the festival of

Chronos, Saturnalia was the

feast at which the

Romans commemorated the dedication of the temple of

Saturn, which originally took place on

17 December, but expanded to a whole week, up to

23 December. A large and important public festival in

Rome, it involved the conventional sacrifices, a couch set

in front of the temple of

Saturn and the untying of the ropes that bound the

statue of Saturn during the rest of the year. Besides the

public

rites there were a series of holidays and customs

celebrated privately. The celebrations included a school

holiday, the making and giving of small presents (saturnalia

et sigillaricia) and a special market (sigillaria).

Gambling was allowed for all, even slaves during this

period. The

toga was not worn, but rather the synthesis, i.e.

colorful, informal "dinner clothes"; and the

pileus (freedman's hat) was worn by everyone. Slaves

were exempt from punishment, and treated their masters with

disrespect. The slaves celebrated a banquet: before, with,

or served by the masters. Saturnalia became one of the most

popular

Roman festivals which led to more tomfoolery, marked

chiefly by having masters and slaves ostensibly switch

places, temporarily reversing the social order. In Greek and

Cypriot folklore it was believed that children born

during the festival were in danger of turning into

Kallikantzaros which come out of the earth after the

solstice to cause trouble for mortals. Some would leave

colanders on their doorsteps to distract them until the

sun returned.

[edit]

Seva Zistanê (Kurdish)

The Night of Winter (Kurdish:

Seva Zistanê) is an unofficial holiday celebrated by

communities throughout the

Kurdistan region in the Middle East. The night is

considered one of the oldest holidays still observed by

modern

Kurds and was celebrated by ancient tribes in the region

as a holy day. The holiday falls every year on the Winter

Solstice. Since the night is the longest in the year,

ancient tribes believed that it was the night before a

victory of light over darkness and signified a rebirth of

the Sun. The Sun plays an important role in several ancient

religions still practiced by some Kurds in addition to

Zoroastrianism.

In modern times, communities in the

Kurdistan region still observe the night as a holiday.

Many families prepare large feasts for their communities and

the children play games and are given sweets in similar

fashion to modern-day Halloween practices.

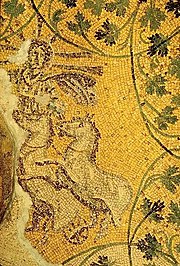

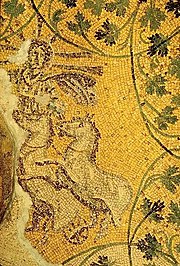

Possible Christ as Sol Invictus riding in his

chariot. Third century mosaic in

Pope Julii's tomb.

Possible Christ as Sol Invictus riding in his

chariot. Third century mosaic in

Pope Julii's tomb.

[edit]

Sol Invictus Festival (3rd

century

Roman Empire)

-

Sol Invictus ("the undefeated Sun") or, more

fully, Deus Sol Invictus ("the undefeated sun god")

was a religious title applied to at least three distinct

divinities during the later

Roman Empire;

El Gabal,

Mithras, and

Sol.

A festival of the birth of the Unconquered Sun (or

Dies Natalis Solis Invicti) was celebrated when the

duration of daylight first begins to increase after the

winter solstice, — the "rebirth" of the sun. The Sol

Invictus festival ran from December 22 through December 25,

which at that time was at the solstice. With the growing

popularity of the Christian cults,

Jesus of Nazareth came to adopt much of the recognition

previously given to a sun god, there by, including

Christ into the tradition. This was later condemned by

the early Catholic Church for its pagan practices and

for associating the Christ with the other sun gods.

[edit]

Soyal (Zuni

and

Hopi of

North America)

-

Soyalangwul is the winter solstice ceremony of the

Zuni and the Hopitu Shinumu, "The Peaceful Ones", also

known as the

Hopi Indians. It is held on December 21st, the shortest

day of the year. The main purpose of the ritual is to

ceremonially bring the sun back from its long winter

slumber. It also marks the beginning of another cycle of the

Wheel of the Year, and is a time for purification. Pahos

(prayer sticks) are made prior to the Soyal ceremony, to

bless all the community, including their homes, animals, and

plants. The kivas (sacred underground ritual

chambers) are ritually opened to mark the beginning of the

Kachina season.[26][27]

[edit]

Te?ufat ?ebet (Jewish)

-

Tekufah

Tevet is one of four Tekufot (Hebrew:

??????), solstices and

equinoxes recognized by the

Talmudical writers. Te?ufat

Tevet, the winter solstice, the beginning of winter, or

"'et ha-?oref" (stripping-time) was when

Jephthah sacrificed his daughter . A long standing

superstition is that on any of the Tekufot, water

that is kept in vessels turned poisonous and must be thrown

out. Some believed the poisoning could be prevented by

placing iron in the water over the Tekufot.[28]

This observations solemness is unlike its proximal holiday,

Hanukkah, a celebration which became prominent as it was

influenced by Christmas traditions.

[edit]

Wayeb (Maya)

Wayeb' or Uayeb, referencing the unlucky

god N, were actually five nameless days leading up to

the end of the

Haab, the solar

Maya calendar. It was thought to be a dangerous time in

which there were no divisions between the mortal and

immortal worlds, and deitys were free to cause disaster if

they willed it. To ward off the spirits, the Maya had a

variety of customs they practiced during this period. For

example, people avoided leaving their houses or grooming

their hair.

Calendar Round rituals would be held at the end of each

52 year round (coincidence of the three Maya calendars),

4 wayeb to 1 Imix 0 Pop, with all fires

extinguished, old pots broken, and a new fire ceremony

symbolizing a fresh start. The next Calendar Round will be

on the winter solstice of 2012, beginning a new

baktun. Haab' observations are still held by Maya

communities in the highlands of

Guatemala.[29]

[edit]

Yule, Jul, Jól, Joul, Joulu,

Jõulud, Géol, Geul (Viking

Age,

Northern Europe)

-

Originally the name Giuli signified a 60 day tide

beginning at the lunar midwinter of the late Scandinavian

Norse and

Germanic tribes. The arrival of Juletid thus came

to refer to the midwinter celebrations. By the late

Viking Age, the Yule celebrations came to specify

a great solstitial Midwinter festival that amalgamated the

traditions of various midwinter celebrations across Europe,

like Mitwinternacht, Modrasnach,

Midvinterblot, and the

Teutonic solstice celebration, Feast of the Dead.

A documented example of this is in

960,

when King Håkon of

Norway signed into law that Jul was to be

celebrated December 25, to align it with the Christian

celebrations. For some Norse sects,

Yule logs were lit to honor

Thor, the god of thunder. Feasting would continue until

the log burned out, three or as many as twelve days. The

indigenous lore of the

Icelandic Jól continued beyond the

Middle Ages, but was condemned when the

Reformation arrived. The celebration continues today

throughout

Northern Europe and elsewhere in name and traditions,

for

Christians as representative of the

nativity of Jesus, and for others as a cultural winter

celebration.[30]

[edit]

Yule, Yulefest, Jul, Jól, Joulu

(secular,

Anglospherean,

Northern European and

Germanic cultures)

-

- Amongst

Anglosphereans, Yule or Yuletide is

also a celebrated

secular alternative to "Christmas", commonly

occurring on the winter solstice or December 24th and

25th, in the northern hemisphere. In the southern

hemisphere it is often celebrated on the winter solstice

or some time through early

July. The earliest recorded

Australian midwinter bonfire was lit in

Moonta, the night leading into

June 24,

1862, by

Cornish immigrants carrying on the European

Midsummer tradition. The midwinter bonfire holiday

also began in

Burra soon after. Currently, Yulefest is

observed by various Australians, often starting on a

weekend in late

June. The contemporary Scandinavian Jul,

Julfest, Jól or Joulu is primarily a

cultural observance and does not distinguish between the

Germanic feast, the Christian Christmas, the secular

Yule, the Neopagan Yule, or the

pre-Indo-European winter solstice celebration and is

also occasionally used to denote other holidays in

December, e.g., "jødisk jul" or "judisk jul" (tr.

"Jewish Yule") for

Hanukkah.[31]

[edit]

Jul (Germanic

Neopaganism)

-

- In

Germanic Neopagan sects, Yule is celebrated with

gatherings that often involve a meal and gift giving.

Further attempts at reconstruction of surviving accounts

of historical celebrations are often made, a hallmark

being variations of the traditional. However it has been

pointed out that this is not really reconstruction as

these traditions never died out - they have merely

removed the Christian elements from the celebration and

replaced the event at the solstice.

- The Icelandic

Ásatrú and the

Asatru Folk Assembly in the US recognize Jól

or Yule as lasting for 12 days, beginning on the

date of the winter solstice.[32]

[edit]

Yule (Wiccan)

-

- In

Wicca, a form of the holiday is observed as one of

the eight solar holidays, or

Sabbat. In most Wiccan sects, this holiday is

celebrated as the rebirth of the Great God, who is

viewed as the newborn solstice sun. Although the name

Yule has been appropriated from Germanic paganism,

the celebration itself is of modern origin.

[edit]

Zagmuk, Sacaea (Ancient

Mesopotamia,

Sumerian,

Babylonian)

-

Adapting the Egyptian Osiris Celebrations, the

Babylonians held the annual renewal or new year

celebration, the Zagmuk Festival. It Lasted 12 days

overlapping the winter solstice or

vernal equinox in its center peak. It was a festival

held in observation of the sun god,

Marduk's battle over darkness. The Babylonians held both

land and river

parades. Sacaea, as

Berossus referred to it, had festivals characterized

with a subversion of order leading up to the new year.

Masters and slaves interchanged, a mock king was crowned and

masquerades clogged the streets. This has been a

suggested precursor to the Festival of Kronos,

Saturnalia and possibly

Purim.[33][34]

[edit]

Ziemassvetki (Latvian,

Baltic,

Romuva)

-

In ancient

Latvia, Ziemassvetki, meaning winter festival,

was celebrated on

December 24 as one of the two most important holidays,

the other being

Jani. Ziemassvetki celebrated the birth of

Dievs, the highest god of

Latvian mythology. The two weeks before Ziemassvetki are

called

Velu laiks, the "season of ghosts." During the festival,

candles were lit for

Dievinš and a fire kept burning until the end, when its

extinguishing signaled an end to the unhappiness of the

previous year. During the ensuing feast, a space at the

table was reserved for Ghousts, who was said to arrive on a

sleigh. during the feast, certain foods were always eaten:

bread,

beans,

peas,

pork and

pig

snout and feet. Carolers (Budeli) went door to door

singing songs and eating from many different houses. The

holiday was later adapted by Christians in the

middle ages. It is now celebrated on the 24th, 25th and

26th of December and largely recognized as both a Christian

and secular cultural observance.

Lithuanians of the

Romuva religion continue to celebrate a variant of the

original

polytheistic holiday.

[edit]

See also

[edit]

Winter observances

[edit]

Sources

- ^

ReligiousTolerance.org

- ^

An Ancient Holiday History Channel

- ^

Q&A on Bright Light Therapy Columbia

University

- ^

Yale-New Haven Psychiatric Hospital

- ^

University of Connecticut

- ^

School of the Seasons

- ^

Madsen, Loren. Despite Everything Davka.org

- ^

Celtic Yule Rituals ADF Druid Fellowship

- ^

The Iranian, History

- ^

New York Metropolitan Museum

- ^

UK History

-

^

Mostrey, Dimitri InfoPeru.com

- ^

Minnesota University

-

^

Winter solstice Adventure Calendar

-

^

Koleda

- ^

Dies Alcyoniae: The Invention of Bellini's Feast of

the Gods, by Anthony Colantuono College Art

Association, Inc. The Art Bulletin. 1991. Vol. 73,

No. 2, p. 246

- ^

Correspondences between the Delian and Athenian

Calendars in the Years 433 and 432 B. C., by Allen

B. West. American Journal of Archaeology. 1934.

Vol.38, No. 1, p.9

- ^

The Miracle of the Wine at Dionysos' Advent; On the

Lenaea Festival, by J. Vürtheim The Classical

Quarterly, 1920. Vol. 14, No. 2, p.94

- ^

Griffith University, The Centre for Public Culture

and Ideas

- ^

Margaret Read MacDonald (1992). The Folklore of

World Holidays, Chapter: circa December 21.

- ^

Jones, Prudence & Pennick, Nigel. A History of Pagan

Europe. Routledge; NY,NY (1997)

pp.122-125.

- ^

Internet Sacred Texts Archive

-

^ Hottes,

Alfred Carl, 1001 Christmas Facts and Fancies, NY:

De La Mare,

1937.

- ^

Kelly, Mary B. Goddesses and Their Offspring, NY:

Binghamton (1990)

- ^

The Iranian, History

- ^

Bahti, Tom. "Southwestern Indian Ceremonials". KC

Publications (1970)

p36-40.]

- ^

HOPI: The Real Thing

- ^

Abudarham, Sha'ar ha-Te?ufot, p. 122a, Venice, 1566

- ^

Foster, Lynn V. Handbook to Life in the Ancient

Mayan World. New York: Facts on File. (2002).

- ^

Jones, Prudence & Pennick, Nigel. A History of Pagan

Europe. Routledge; NY,NY (1997)

pp.122-125.

- ^

Samuels, Brian. Aspects of Australian Folklife

- ^

Asatru Folk Assembly

- ^

Ruano, Teresa Sacaea-Saturnalia.

Candlegrove.com

- ^

Morrison, Dorothy. Yule: A Celebration of Light and

Warmth. Llewellyn Publications (2000)

Categories:

History articles needing expert attention |

Articles needing expert attention |

Winter festivals |

Winter holidays |

Secular holidays |

December observances |

June observances |

Astronomical events

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- This article is about the astronomical and cultural event of winter's solstice, also known as midwinter. For other uses, see Winter solstice (disambiguation), Midwinter (disambiguation) or also see Solstice.

| Winter Solstice | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Fire kept burning through the longest night of the year | |

| Also called | Midwinter, DongZhì, Yule, Sabe Cele/Yalda, Soyal, Te?ufat ?ebet, Seva Zistanê, Solar New Year, Longest Night |

| Observed by | Various cultures, ancient and modern |

| Type | Cultural, Seasonal, Astronomical |

| Significance | Astronomically marks the middle or beginning of winter, interpretation varies from culture to culture, but most hold a recognition of rebirth |

| Date | The

Solstice of

Winter December 21 or 22 (NH) June 21 or 22 (SH) |

| 2007 date |

December 22 (UTC

North) June 21 (UTC South) |

| 2008 date |

December 21 (UTC

North) June 20 (UTC South) |

| Celebrations | Festivals, spending time with loved ones, feasting, singing, dancing, fire in the hearth |

| Related to | Winter Festivals and the Solstice |

| year | Solstice June |

Solstice Dec |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| day | time | day | time | |

| 2007 | 21 | 18:06 | 22 | 06:08 |

| 2008 | 20 | 23:59 | 21 | 12:04 |

| 2009 | 21 | 05:45 | 21 | 17:47 |

| 2010 | 21 | 11:28 | 21 | 23:38 |

| 2011 | 21 | 17:16 | 22 | 05:30 |

| 2012 | 20 | 23:09 | 21 | 11:11 |

| 2013 | 21 | 05:04 | 21 | 17:11 |

| 2014 | 21 | 10:51 | 21 | 23:03 |

The winter solstice occurs at the instant when the Sun's position in the sky is at its greatest angular distance on the other side of the equatorial plane as the observer. Depending on the shift of the calendar, the event of the Winter solstice occurs sometime between December 20 and 23 each year in the Northern hemisphere, and between June 20 and 23 in the Southern Hemisphere, and the winter solstice occurs during either the shortest day or the longest night of the year (not to be confused with the darkest day or nights). Though the Winter Solstice lasts an instant, the term is also used to refer to the full 24-hour period.

Worldwide, interpretation of the event has varied from culture to culture, but most cultures have held a recognition of rebirth, involving holidays, festivals, gatherings, rituals or other celebrations around that time.[1]

The word solstice derives from Latin sol (Sun) and sistere (stand still), Winter Solstice meaning Sun stand still in winter.

[edit] Date

Calendrically, in most countries the time of the winter solstice is considered as midwinter. This is evident in calendars as far back as Ancient Egypt, whose system of seasons was gauged according to the flooding of the Nile. For Celtic countries, such as Ireland, the calendarical winter season has traditionally begun November 1 on All Hallows or Samhain. Winter ends and spring begins on Imbolc or Candlemas, which is February 1 or 2. This calendar system of seasons may be based on the length of days exclusively. Most East Asian cultures define the seasons by solar terms, with Dong zhi at the Winter solstice as the middle or "Extreme" of winter. This system is based on the sun's tilt. Some Midwinter festivals have occurred according to lunar calendars and so took place on the night of Hoku (Hawaiian: the full moon closest to the winter solstice). And many European solar calendar Midwinter celebrations still centre upon the night of December 24th leading into the 25th in the north, which was considered to be the winter solstice upon the establishment of the Julian calendar. In Jewish culture, Te?ufat Tevet, the day of the winter solstice, is historically known as the first day of the "stripping time" or winter season. Persian cultures also recognize it as the beginning of winter. Recently, many United States calendars have marked the date on which the winter solstice occurs as the Astronomical First day of winter as a reference to the Tekufah.

Since the time when the 25th was established as the

solstice in Europe the difference between the Julian

calendar year (365.2500 days) and the

tropical year (365.2422 days) moved the day associated

with the actual astronomical solstice forward approximately

three days every four centuries until

1582 when

Pope Gregory XIII changed the calendar bringing the

northern winter solstice to around December 21st. In the

Gregorian calendar the solstice still moves around a

bit, but only about one day in 3000 years.

The figures above show the differences between the Gregorian

calendar (Figure 1: using 1 leap year per 4 years) and

Persian Persian Jalali calendar (Figure 2: using the

33-year arithmetic approximation) in reference to the actual

yearly time of the winter solstice of the northern

hemisphere, the December solstice. The Y axis is

"days error" and the X axis is Gregorian calendar years.

Each point represents a single date on a given year. The

error shifts by about 1/4 day per year, and is corrected by

a leap year every 4th year regularly, and in the case of the

Persian calendar also one 5 year leap period to complete a

33-year cycle, keeping the Persian winter solstice holiday

on the same day every year.

[edit] History & Cultural significance

Astronomical events, which during ancient times allowed for the scheduling of mating, sowing of crops and metering of winter reserves between harvests, show how various cultural mythologies and traditions have arisen. On the night of Winter Solstice, as seen from a northern sky, the three stars in Orion's belt align with the brightest star in the Eastern sky Sirius to show where the Sun will rise in the morning after Winter Solstice. Until this time, the Sun has exhibited since Summer Solstice a decreasing arc across the Southern sky. On Winter Solstice, the Sun ceased to decline in the sky and the length of daylight reaches its minimum for three days. At such a time, the Sun begins its ascent and days grow longer. Thus the interpretation by many cultures of a sun reborn and a return to light. This return to light is again celebrated (at the vernal equinox, when the length of day equals that of night.

The solstice itself may have remained a special moment of the annual cycle of the year since neolithic times. This is attested by physical remains in the layouts of late Neolithic and Bronze Age archaeological sites like Stonehenge in Britain and Brú na Bóinne (New Grange) in Ireland. The primary axes of both of these monuments seem to have been carefully aligned on a sight-line framing the winter solstice sunrise (New Grange)and the winter solstice sunset (Stonehenge). The winter solstice may have been immensely important because communities were not assured to live through the winter, and had to be prepared during the previous nine months. Starvation was common in winter between January to April, also known as the famine months. In temperate climates, the midwinter festival was the last feast celebration, before deep winter began. Most cattle were slaughtered so they would not have to be fed during the winter, so it was nearly the only time of year when a supply of fresh meat was available. The majority of wine and beer made during the year was finally fermented and ready for drinking at this time. The concentration of the observances were not always on the day commencing at midnight or at dawn, but the beginning of the pre-Romanized day, which falls on the previous eve.[2]

[edit] Explanations for parallel traditions

[edit] Symbolic

Often since the event is observed as the reversal of the Sun's ebbing presence in the sky, concepts of the birth or rebirth of sun gods have been common and, in cultures using winter solstitially based cyclic calendars, the year as reborn has been celebrated with regard to life-death-rebirth deities or new beginnings such as Hogmanay's redding, a New Years cleaning tradition. Also reversal is another usual theme as in Saturnalia's slave and master reversals.

[edit] Migration and appropriation

Many outside traditions are often adopted by neighboring or invading cultures. Some historians will often assert that many traditions are directly derived from previous ones rooting all the way back to those begun in the cradle of civilization or beyond, much in a way that correlates to speculations on the origins of languages.

[edit] Therapeutic

Even in modern cultures these gatherings are still valued for emotional comfort, having something to look forward to at the darkest time of the year. This is especially the case for populations in the near polar regions of the hemisphere. The depressive psychological effects of winter on individuals and societies for that matter, are for the most part tied to coldness, tiredness, malaise, and inactivity. Winter weather, plus being indoors causes negative ion deficiency which decreases serotonin levels resulting in depression and tiredness. Also, getting insufficient light in the short winter days increases the secretion of melatonin in the body, off balancing the circadian rhythm with longer sleep. Exercise, light therapy, increased negative ion exposure (which can be attained from plants and well ventilated flames burning wood or beeswax) can reinvigorate the body from its seasonal lull and relieve winter blues by shortening the melatonin secretions, increasing serotonin and temporarily creating a more even sleeping pattern. Midwinter festivals and celebrations occurring on the longest night of the year, often calling for evergreens, bright illumination, large ongoing fires, feasting, communion with close ones, and evening physical exertion by dancing and singing are examples of cultural winter therapies that have evolved as traditions since the beginnings of civilization. Such traditions can stir the wit, stave off malaise, reset the internal clock and rekindle the human spirit.[3][4]

[edit] Observances

The following is an alphabetical list of observances

believed to be directly linked to the winter solstice. For

other Winter observances see

List of winter festivals.:

[edit] Amaterasu celebration, Requiem of the Dead (7th century Japan)

In late seventh century Japan, festivities were held to celebrate the reemergence of Amaterasu or Amateras (Hindu), the sun goddess of Japanese mythology, from her seclusion in a cave. Tricked by the other gods with a loud celebration, she peeks out to look and finds the image of herself in a mirror and is convinced by the other gods to return, bringing sunlight back to the universe. Requiems for the dead were held and Manzai and Shishimai were performed throughout the night, awaiting the sunrise. Aspects of this tradition have continued to this day on New Years.[5]

[edit] Beiwe Festival (Sámi of Northern Fennoscandia)

- See also: Beiwe

The Saami, indigenous people of Finland, Sweden and Norway, worship Beiwe, the sun-goddess of fertility and sanity. She travels through the sky in a structure made of reindeer bones with her daughter, Beiwe-Neia, to herald back the greenery on which the reindeer feed. On the winter solstice, her worshipers sacrifice white female animals, and with the meat, thread and sticks, bed into rings with ribbons. They also cover their doorposts with butter so Beiwe can eat it and begin her journey once again.[6]

[edit] Choimus, Chaomos (Kalash of Pakistan)

In the ancient traditions of the Kalash people of Pakistan, during winter solstice, a demigod returns to collect prayers and deliver them to Dezao, the supreme being. "During this celebrations women and girls are purified by taking ritual baths. The men pour water over their heads while they hold up bread. Then the men and boys are purified with water and must not sit on chairs until evening when goat's blood is sprinkled on their faces. Following this purification, a great festival begins, with singing, dancing, bonfires, and feasting on goat tripe and other delicacies".[7]

[edit] Christmas, Natalis Domini (4th century Rome, 11th century England, Christian)

Christmas or Christ's Mass is one of most popular Christian celebrations as well as one of the most globally recognized midwinter celebrations. Christmas is the celebration of the birth of the God Incarnate or Messiah, Yeshua of Nazareth, later known as Jesus Christ. The birth is observed on December 25th, which was the winter solstice upon establishment of the Julian Calendar in 45 BC. Banned by the Catholic Church in its infancy as a pagan, or non-Abrahamic, practice stemming out of the Sol Invictus celebrations, Christians revitalized its recognition as an authentic Christian festival in various cultures within the past several hundred years, preserving much of the folklore and traditions of local pagan festivals. So today, the old festivals such as Jul, ?????? and Karácsony, are still celebrated in many parts of Europe, but the Christian Nativity is now often representational of the meaning. This is why Yule and Christmas are considered interchangeable in Anglo-Christendom. Universal activities include feasting, midnight masses and singing Christmas carols about the Nativity. Good deeds and gift giving in the tradition of St. Nicholas by not admitting to being the actual gift giver is also observed by some countries. Many observe the holiday for twelve days leading up to the Epiphany.

[edit] Deuorius Riuri (Gaul)

Deuorius Riuri was the annual great divine winter feast, observed by the Coligny Calendar. The lunisolar Coligney Midwinter returned to solar alignment every two and a half years.[8]

[edit] Deygan (Zoroastrian)

The last day of the Persian month Azar is the longest night of the year, when the forces of Ahriman are assumed to be at the peak of their strength. While the next day, the first day of the month Dey known as khoram ruz or khore ruz (the day of sun) belongs to Ahura Mazda, the Lord of Wisdom. Since the days are getting longer and the nights shorter, this day marks the victory of Sun over the darkness. The occasion was celebrated in the ancient Persian Deygan Festival dedicated to Ahura Mazda, and Mithra on the first day of the month Dey.[9]

[edit] DongZhì Festival, Toji Festival (East Asia, Vietnam, and Buddhist)

The Winter Solstice Festival or The Extreme of Winter (Chinese and Japanese: ??; Korean: ??; Vietnamese: Ðông chí) (Pinyin: Dong zhì), (Romaji: Toji) is one of the most important festivals celebrated by the Chinese and other East Asians during the dongzhi solar term on or around December 21 when sunshine is weakest and daylight shortest; i.e., on the first day of the dongzhi solar term. The origins of this festival can be traced back to the Yin and Yang philosophy of balance and harmony in the cosmos. After this celebration, there will be days with longer daylight hours and therefore an increase in positive energy flowing in. The philosophical significance of this is symbolized by the I Ching hexagram fù (?, "Returning"). Traditionally, the Dongzhi Festival is also a time for the family to get together. One activity that occurs during these get togethers (especially in the southern parts of China and in Chinese communities overseas) is the making and eating of Tangyuan (??, as pronounced in Cantonese; Mandarin Pinyin: Tang Yuán) or balls of glutinous rice, which symbolize reunion.

[edit] Goru (Dogon of Mali)

Goru is the (December) winter solstice ceremony of the Pays Dogon of Mali. It is the last harvest ritual and celebrates the arrival of humanity from the sky god, Amma, via Nommo inside the Aduno Koro, or the "Ark of the World".[10]

[edit] Hogmanay (Scotland)

The New Years Eve celebration of Scotland is called Hogmanay. The name derives from the old Scots name for Yule gifts of the Middle Ages. The early Hogmanay celebrations were originally brought to Scotland by the invading and occupying Norse who celebrated a solstitial new year (England celebrated the new year on March 25th). In 1600 with the Scottish application of the January 1st New year and the churches persistent abolition of the solstice celebrations, the holiday traditions moved to December 31. The festival is still referred to as the Yules by the Scots of the Shetland Islands who start the festival on December 18th and hold the last tradition, (a Troll chasing ritual) on January 18th. The most widespread Scottish custom is the practice of first-footing which starts immediately after midnight on New Years. This involves being the first person (usually tall and dark haired) to cross the threshold of a friend or neighbor and often involves the giving of symbolic gifts such as salt (less common today), coal, shortbread, whisky, and black bun (a fruit pudding) intended to bring different kinds of luck to the householder. Food and drink (as the gifts, and often Flies cemetery) are then given to the guests.[11]

[edit] Inti Raymi (Inca, Peru)

The Inti Raymi or Festival of the Sun was a religious ceremony of the Inca Empire in honor of the sun god Inti. It also marked the winter solstice and a new year in the Andes of the Southern Hemisphere. One ceremony performed by the Inca priests was the tying of the sun. In Machu Picchu there is still a large column of stone called an Intihuatana, meaning "hitching post of the sun" or literally for tying the sun. The ceremony to tie the sun to the stone was to prevent the sun from escaping. The Spanish conquest, never finding Machu Picchu, destroyed all the other intihuatana, extinguishing the sun tying practice. The Catholic Church managed to suppress all Inti festivals and ceremonies by 1572. Since 1944, a theatrical representation of the Inti Raymi has been taking place at Sacsayhuamán (two km. from Cusco) on June 24 of each year, attracting thousands of local visitors and tourists. The Monte Alto culture may have also had a similar tradition.[12][13]

[edit] Junkanoo, Jonkonnu, John Canoe (West Africa, Bahamas, Jamaica, 19th-century North Carolina)

Junkanoo, in the Bahamas, Junkunno or Jonkanoo, in Jamaica, is a fantastic masquerade, parade and street festival, believed to be of West African origin. It is traditionally performed through the streets towards the end of December, and involves participants dressed in a variety of fanciful costumes, such as the Cow Head, the Hobby Horse, the Wild Indian, and the Devil. The parades are accompanied by bands usually consisting of fifes, drums, and coconut graters used as scrapers, and Jonkanoo songs are also sung. A similar practice was once common in coastal North Carolina, where it was called John Canoe, John Koonah, or John Kooner. John Canoe was likened to the wassailing tradition of medieval Britain. Both John Canoe and wassailing bear strong resemblance to the social inversion rituals that marked the ancient Roman celebration of Saturnalia.

[edit] Karachun (Ancient Western Slavic)

Karachun, Korochun or Kracún was a Slavic holiday similar to Halloween as a day when the Black God and other evil spirits are most potent. It was celebrated by Slavs on the longest night of the year. On this night, Hors, symbolising old sun, becomes smaller as the days become shorter in the Northern Hemisphere, and dies on December 22nd, the December solstice. It is said to be defeated by the dark and evil powers of the Black God. In honour of the god, Hors, Slavs danced a ritual chain-dance which was called the horo. Traditional chain-dancing in Bulgaria is still called horo. In Russia and Ukraine, it is known as khorovod. On December 23rd Hors is resurrected and becomes the new sun, Koleda. Modern scholars tend to associate this holiday with the ancestor worship. On this day, Western Slavs burned fires at cemeteries to keep their loved ones warm, they organized dinings in the honor of the dead so as they would not suffer from hunger. They also lit wooden logs at local crossroads.

[edit] Koleda, ??????, Sviatki, Dazh Boh (Ancient Eastern Slavic and Sarmatian)

| This article or section is

in need of attention from an expert on the subject.

WikiProject History or the

History Portal may be able to help recruit one. |

In ancient Slavonic cultures, the festival of Kaleda began at Winter Solstice and lasted for ten days. In Russia, this festival was later applied to Christmas Eve but most of the practices were lost after the Soviet Revolution. Each family made a fire in their hearth and invited their personal household Gods to join in the festivities. Children disguise themselves on evenings and nights and as Koledari, visited houses and sang wishes of good luck, like Shchedryk, to hosts. As a reward, they were given little gifts, a tradition called Kolyadovanie, much like the old wassailing or mummers Tradition.[14][15]

[edit] Lenæa, Brumalia (Ancient and Hellenistic Greece, Roman Kingdom)

In the Aegean civilizations, the exclusively female midwinter ritual, Lenaea or Lenaia, was the Festival of the Wild Women. In the forest, a man or bull representing the harvest god, Dionysus, was torn to pieces and eaten by Maenads. Later in the ritual, a baby, representing Dionysus reborn, was presented. The Ageans dedicated their first month of the Delian calendar, Lenaion, to the festival's name. By classical times, the human sacrifice had been replaced by that of a goat and the women's role had changed to that of funeral mourners and observers of the birth. Wine miracles were performed by the priests, in which priests would seal water or juice into a room overnight and the next day it would have turned into wine. The miracle was said to have been performed by Dionysus and the Lenaians. By the 5th century BC the ritual had become a Gamelion festival for theatrical competitions, often held in Athens in the Lenaion theater. The festival influenced Brumalia which was an ancient Roman solstice festival honoring Bacchus, generally held for a month and ending December 25. The festival included drinking and merriment. The name is derived from the Greek word bruma, meaning "shortest day", though the festivities almost always occurred at night.[16][17][18]

[edit] Lucia, Feast of St. Lucy (Ancient Swedish, Scandinavian Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox)

Lucia or Lussi Night happened on December 13, what was supposed to be the longest night of the year. The feast was later appropriated by the Catholic Church in the 16th century as St. Lucy's Day. It was believed in the folklore of Sweden that if people, particularly children, did not carry out their chores, the female demon, the Lussi or Lucia die dunkle would come to punish them.[19]

[edit] Makara Sankranti (India and Nepal, Hindu)

Makara Sankranti, celebrated at the beginning of Uttarayanais, is the only Hindu festival which is based on the Celestial calendar rather than the Lunar calendar. The Zodiac having drifted from the solar calendar has caused the festival to now occur in mid January. In Assam it is called Magh Bihu (the First day of Magh), in Punjab, Lohri and in Maharshtra it is called Tilgul, but the place where it is celebrated with much pomp is Andhra Pradesh, where the festival is celebrated for 3 days and is more of a cultural festival unlike an auspicious day as in other parts of india. In some parts of India, the festival is celebrated by taking dips in the Ganga or any river and offering water to the Sun god. The dip is said to purify the self and bestow punya. In many countries, families fly kites from their roofs all day and into the night. In Assam on Bihu Eve or Uruka families build bhelaghar, house like structures, and separate large bhelaghar are built by the community as a whole. Twine of sorts are tied around fruit trees. Out of tradition, fuel is stolen for the final ceremony, when all the bhelaghar are burned. Their remains are then placed at the fruit trees. Special puja is offered as a thanksgiving for good harvest. Since the festival is celebrated in the mid winter, the food prepared for this festival are such that they keep the body warm and give high energy. Laddu of til made with Jaggery (Gur)is specialty of the festival.[20]

[edit] Meán Geimhridh, Celtic Midwinter (Celtic, Ancient Welsh, Neodruidic)

Meán Geimhridh (Irish tr: Midwinter) or Grianstad an Gheimhridh (Ir tr: Winter solstice) is a name sometimes used for hypothetical Midwinter rituals or celebrations of the Proto-Celtic Neolithic tribes, Celts, and late Druids. In Ireland's calendars, the solstices and equinoxes all occur at about midpoint in each season. The passage and chamber of Newgrange (Pre-Celtic or possibly Proto-Celtic 3,200 BC), a tomb in Ireland, are illuminated by the winter solstice sunrise. A shaft of sunlight shines through the roof box over the entrance and penetrates the passage to light up the chamber. The dramatic event lasts for 17 minutes at dawn from the 19th to the 23rd of December. The point of roughness is the term for the winter solstice in Wales which in ancient Welsh mythology, was when Rhiannon gave birth to the sacred son, Pryderi.

[edit] Wren day (Celtic, Irish, Welsh, Manx)

- For an unknown period, Lá an Dreoilín or Wren day has been celebrated in Ireland, The Isle of Man and Wales on December 26. Crowds of people, called wrenboys, take to the roads in various parts of Ireland, dressed in motley clothing, wearing masks or straw suits and accompanied by musicians supposedly in remembrance of the festival that was celebrated by the Druids. Previously the practice involved the killing of a wren, and singing songs while carrying the bird from house to house, stopping in for food and merriment.

[edit] Alban Arthan (Neodruidic)

- In England, during the 18th century, there was a revival of interest in Druids. Today, amongst Neo-druids, Alban Arthan (Welsh tr. light of Winter but derived from Welsh poem, Light of Arthur) is celebrated on the winter solstice with a ritualistic festival, and gift giving to the needy.

[edit] Midvinterblót (Swedish folk religion)

In Sweden and many surrounding parts of Europe, polytheistic tribes celebrated a Midvinterblot or mid-winter-sacrifice, featuring both animal and human sacrifice. The blot was performed by goði, or priests, at certain cult sites, most of which have churches built upon them now. Midvinterblot paid tribute to the local gods, appealing to them to let go winter's grip. The folk tradition was finally abandoned by 1200, due to missionary persistence.

[edit] Modranicht, Modresnach (Anglo-Saxon, Germanic)

The Night of Mothers or Mothers' Night was an Anglo-Saxon and Germanic feast. It was believed that dreams on this night foretold events in the upcoming year. While it may originally have occurred the night before Samhain according to a lunar calendar, it has moved around quite a bit in the year. By 730, It was thought by Bede to be observed by the Anglicans on the winter solstice. After the reemergence of Christmas in Britain it was recognized by many as one of the 12 Days of Christmas.[21][22]

[edit] Perchta ritual (Germania, Alps)